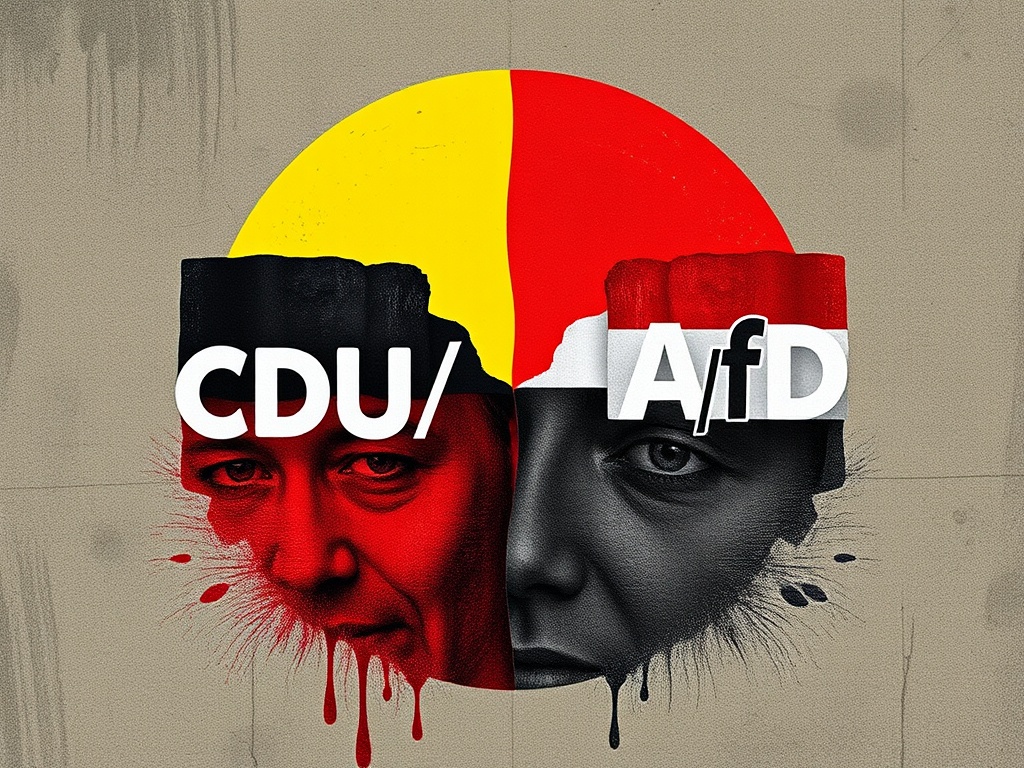

Friedrich Merz’s CDU/CSU Triumphs Amidst AfD’s Resurgence

In a significant turn of events, Friedrich Merz’s conservative party, the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU), emerged victorious in the recent German elections held on Sunday. However, the spotlight was predominantly captured by the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party, which remarkably doubled its share of the vote, securing second place. The CDU/CSU achieved nearly 28.6 percent of the total votes, while the AfD garnered an impressive 20.8 percent, marking a substantial increase from the 12.6 percent it received in the 2021 elections.

With this electoral victory, Merz now faces the challenge of forming a government, likely in coalition with the third-placed Social Democrats (SPD), led by current Chancellor Olaf Scholz, who recorded the lowest vote share for their party since World War II at 16.4 percent. In this context, The i Paper delves into the implications of the AfD’s rising popularity for both its opposition within Germany and its impact on the European Union, Ukraine, and NATO.

The Emergence of the AfD: Immigration as a Catalyst for Growth

The AfD was established in 2013 as a Eurosceptic party in response to the financial crisis, opposing Germany’s financial bailouts of several EU countries, including Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain. Initially, the AfD endorsed political asylum for those facing persecution and steered clear of extreme anti-immigrant or anti-Islam sentiments. However, it has since pivoted towards hardline, far-right positions to capitalize on growing anxieties surrounding Germany’s increasing immigrant and Muslim populations.

The 2015-16 migrant crisis, during which a significant influx of refugees, particularly from Syria, entered the EU, was pivotal in propelling the AfD’s political fortunes. Dan Hough, a Politics Professor at the University of Sussex, noted, “The AfD really began to pose a threat to other parties after 2015-16 when Angela Merkel opened Germany’s doors to over a million asylum seekers from North Africa and the Middle East. That was the turning point.”

This shift to the right caused a rift within the party, leading to the departure of senior members, including its founder, Bernd Lucke. The party’s radicalization was accelerated by a series of violent incidents involving migrants, including a tragic knife attack in Aschaffenburg that resulted in the deaths of a two-year-old boy and a man trying to save him. Similar incidents in cities like Magdeburg and Berlin have further stoked public outrage and calls for stricter immigration policies.

In the lead-up to the election, Merz broke a long-standing political taboo by proposing tightened asylum policies, which gained narrow support in the Bundestag from the AfD. The party has also adopted the controversial notion of “remigration,” suggesting mass deportations of individuals from migrant backgrounds, a stance previously rejected by them. Alice Weidel, co-leader of the AfD, expressed support for large-scale repatriations, stating, “If it’s going to be called remigration, then that’s what it’s going to be: remigration.”

Despite attempts to distance herself from past controversies, Weidel’s comments reflect a broader normalization of radical immigration views within German politics. According to Tarik Abou-Chadi, a Professor at the University of Oxford, the AfD’s success is partly due to the gradual rightward shift of other political parties, which has inadvertently legitimized the AfD’s positions.

Economic Struggles Bolster AfD Support

The AfD’s rise can also be attributed to increasing dissatisfaction with Germany’s stagnating economy and political instability. The recent elections were rescheduled, taking place seven months earlier than initially planned, following the collapse of Scholz’s coalition in November. The country has faced economic contraction over the past two years, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which severely impacted Germany’s reliance on Russian gas.

“In these circumstances, it’s easy for a populist party to capitalize on grievances,” noted Professor Hough. However, the negative ramifications of the AfD’s agenda have already manifested in regions where it has gained power. Christoph Meyer, a Professor at King’s College London, pointed out that the party’s dominance in Eastern Germany could hinder economic growth, deterring skilled migrants and Germans from seeking employment in those areas.

AfD’s Stance on the EU

Historically rooted in opposition to the EU, particularly its economic policies, the AfD maintains a strong anti-EU sentiment. Their draft election manifesto proposed that “Germany must leave the European Union and establish a new European community.” Weidel has echoed this sentiment, advocating for a referendum on “Dexit” (a potential German exit from the EU), asserting that if reforms to restore member states’ sovereignty are unattainable, the citizens should decide, similar to the UK’s Brexit vote.

The AfD also aims to dismantle EU climate policies, abandon the euro in favor of reintroducing the deutschmark, and close borders, opposing the Schengen Area rules.

Pro-Russian Sentiments Among AfD Members

According to Professor Hough, the AfD is recognized as the most pro-Russian party within the Bundestag, often echoing Russian propaganda and displaying reluctance to support Ukraine. Germany ranks as Ukraine’s second-largest weapons supplier, trailing only the United States. Senior AfD officials have suggested a reduction in military aid to Ukraine, proposing measures such as requiring UN approval for weapon transfers, a position criticized given Russia’s veto power in the Security Council.

AfD’s Potential Influence Beyond Government

Despite the AfD’s increased vote share, Professor Meyer believes it is unlikely the party will lead a federal government or participate in a coalition. Nonetheless, the AfD could wield significant influence by forming a “blocking minority” for major federal decisions requiring a two-thirds majority, potentially supported by leftist factions.

Even without a majority, the AfD’s ability to shape policy reflects historical precedents; the NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers’ Party) secured only 18 percent of the vote in 1930 and 33 percent in the last free elections in 1932. The current German constitution includes mechanisms in Article 21 to declare parties as hostile to democracy, which could lead to the AfD facing similar scrutiny as the neo-Nazi National Democratic Party (NPD), which was monitored and restricted due to extremist affiliations.

A Historical Perspective on the AfD’s Rise

The ascent of the AfD has ignited concerns due to Germany’s fraught history with authoritarianism and Nazism. The stigmatization of far-right movements has characterized the post-war era. Tim Bale, a Politics Professor at Queen Mary University of London, cautions that while past reactions to far-right movements may have been exaggerated, “this time it really is serious.” He points out that the AfD is not just another populist party; it has not sufficiently distanced itself from its extreme elements.

The party has faced scandals linking it to Nazism, exemplified by remarks from Maximilian Krah, the AfD’s lead candidate for the European elections, who controversially stated that members of the Nazi SS were not necessarily “criminals.” Although he was expelled from the party, such incidents underscore the AfD’s ongoing entanglement with extremist ideologies. The German domestic intelligence services have kept the party under observation due to its pursuit of goals that challenge human dignity and democracy.