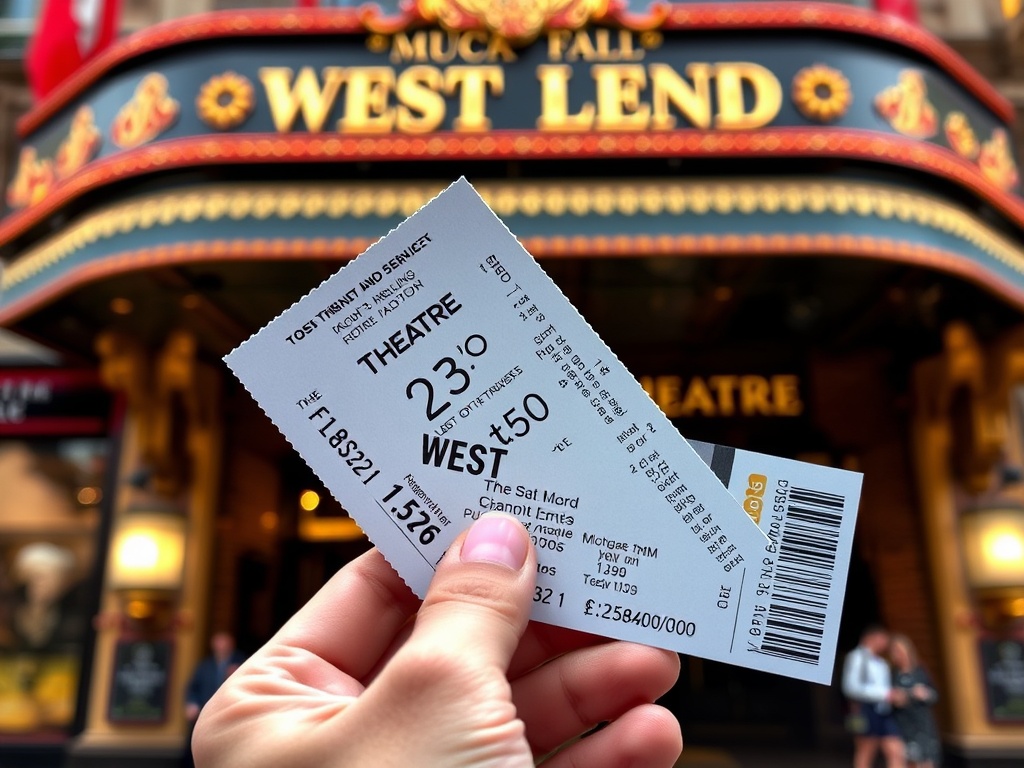

Sound the alarm: the contentious issue of soaring theatre ticket prices has resurfaced in the news. In my recent review of the new West End production of Much Ado About Nothing, featuring the dynamic duo of Tom Hiddleston and Hayley Atwell, I expressed my disbelief when I discovered that the seat I had been allocated in the stalls was priced at a staggering £275. A quick glance at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane’s website reveals that ticket prices escalate to £350 for performances, such as on Friday, March 7. For that amount, you could easily enjoy a weekend getaway in Paris.

This situation has sparked considerable debate and concern: How can such rampant price inflation benefit the theatre industry? How will we introduce the next generation of theatre enthusiasts to this cherished art form? More importantly, how can current fans maintain such an expensive hobby in the face of these rising costs?

These are indeed pressing questions, yet before we spiral into despair, it’s essential to recognize that these prices are typically for last-minute bookings. Many dedicated fans will have purchased their tickets weeks or even months in advance, long before the show received rave reviews, which inevitably triggered a fierce interplay of supply and demand (and theatres increasingly embrace the concept of surge pricing). Furthermore, it’s important to mention that this production, like many others in the West End, offers a variety of discounts, particularly aimed at younger audiences.

That said, what has driven West End ticket prices to such exorbitant heights? The allure of star power is undoubtedly a significant factor, much like it was for Sarah Jessica Parker’s debut on the London stage in Plaza Suite last year. The chance to see renowned actors perform live transforms these productions into “event theatre,” which commands a premium price. In this instance, it is not just Much Ado itself that draws crowds; it is Hiddleston and Atwell who are the main attractions. Conversely, productions that lack star power—such as The Play That Goes Wrong—do not charge such high prices.

The ongoing and often complex contractual obligations of film and, in particular, long-running streaming series mean that star actors typically commit to only limited theatre runs, sometimes as few as 11 weeks. As a result, producers have a limited number of performances to recoup their investment, especially since some high-profile actors, like David Tennant in the recent West End staging of Macbeth, opt out of midweek matinées, further reducing the opportunities to sell tickets. Given these constraints, it’s no surprise that producers set ticket prices as high as they believe the market will bear.

What concerns me most about this issue is not merely the high ticket prices, alarming though they may seem. As I mentioned earlier, these prices reflect the premium rates, and any savvy purchaser can find more affordable options (it’s worth remembering that all subsidized theatres offer various cost-effective membership schemes). My real worry is that potential theatre-goers, even those with a slight interest in experiencing live performances, will see these headline prices and dismiss the art form altogether—perhaps even more troubling, they may decide that their children should not be exposed to theatre. Or, just as detrimentally, they might pay a steep price for one evening out, not enjoy the performance, and subsequently write off theatre as a whole, in a manner that no one would suggest doing with football after witnessing a single poor match.

In many areas of life, patience can be a virtue, especially when it comes to enjoying the theatre. As I write this piece in the early afternoon, I notice that several top stalls seats for Much Ado are available for this evening’s performance. The price? £89.50. While it may not be inexpensive, it represents a return to a more reasonable pricing structure.